© 2024 Tales from Outside the Classroom ● All Rights Reserved

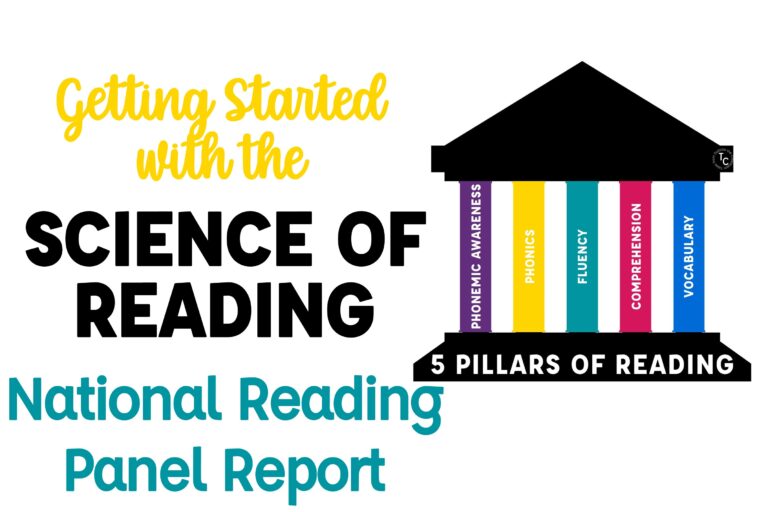

5 Pillars of Reading and the NRP: Getting Started with SoR

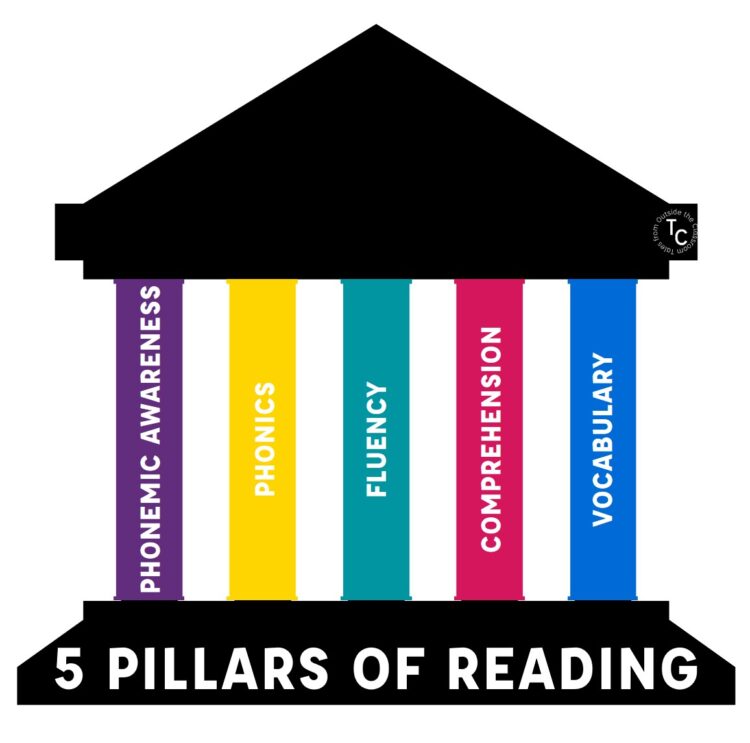

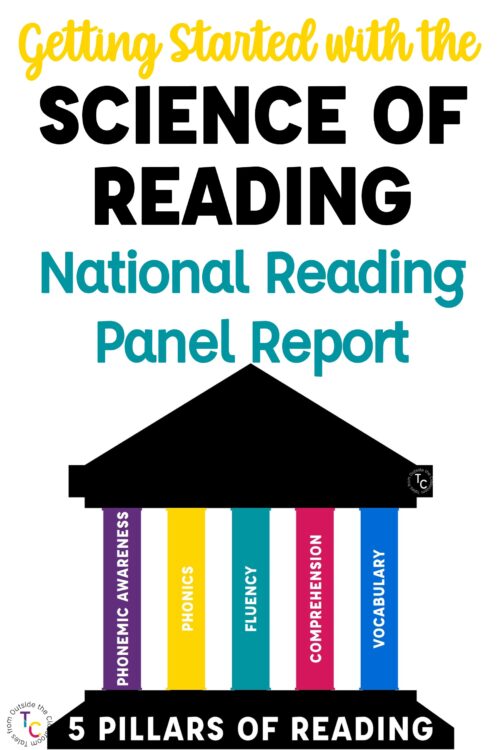

First up in my Getting Started with the Science of Reading series is the 5 Pillars of Reading and the National Reading Panel. In 1997, Congress asked NIH’s branch of Child Development & Behavior to work with the US Department of Education to establish a National Reading Panel. Its intention: to evaluate existing research and evidence to the find best ways to teach our nation’s children to read. They desired an end to the “reading wars”. The 14 member panel included researchers and scientists as well as educators from the field. In 2000, the National Reading Panel concluded its work. They identified five key concepts at the core of every effective reading instruction program: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. These are now known as the 5 pillars of reading.

In this post, I walk through the five pillars of reading, what the NRP findings said about each of these areas, and I give some of my input as a classroom teacher and interventionist. One of the pushbacks against the NRP findings were that the information was not always relevant or immediately applicable to classroom experience. I want to touch on that a little bit. I also highlight some of the post-NRP information that’s related to their findings, while still holding true to the five pillars of reading. Finally, much of the NRP report has been misconstrued and contested. I’ve tried to identify some of these and have included links for further reading at the end.

I think it’s also important to highlight that the Panel was broken down into 3 large subgroups with their own methodologies and focuses. The alphabetics subgroup looked into phonemic awareness and phonics and had their own method of evaluating studies than the other subgroups; the only group to exclusively use meta-analysis. The comprehension subgroup looked at comprehension and vocabulary since they cannot be looked at separately. Finally, the fluency subgroup looked at fluency.

The Five Pillars of Reading

Phonemic Awareness

In my layman’s opinion, the biggest new takeaway for teachers after the NRP report was the need for phonemic awareness instruction. It is clear that phonological skills develop naturally as part of oral language development and are built through typical songs, nursery rhymes, and language play. It is also clear that phonemic awareness develops during the same years when children are learning to read. Evidence has also shown a strong correlation between phonemic awareness abilities and reading achievement. The Panel looked to the need for phonemic awareness instruction.

Children with well-developed phonemic awareness skills tend to be successful readers, while children without these skills are not. -Dr. Timothy Shanahan

But, correlation does not equal causation. The NRP examined 52 studies on phonemic awareness. They showed that phonemic awareness instruction was advantageous to children in the early stages of learning to read, lead to higher achievement in both reading and spelling, and results showed evidence for both word recognition and reading comprehension. The results suggested that phonemic awareness is most effective in kindergarten and first grade. The studies also demonstrated strong improvement in at-risk students receiving instruction. Segmenting and blending were the skills shown to have the strongest advantage. Something to note, phonemic awareness instruction was not effective for improving spelling in disabled readers.

The studies also examined the length of instruction, though the panel did not conclude a specific length of effective instruction due to the variance in studies. From the data, 14-18 hours seems effective for most children, which is a few minutes each day for about half a year. Many children will not need this much instruction, while some students will need more. Once students are able to segment and blend phonemes with ease further instruction isn’t typically needed (Shanahan, 2005).

The most important takeaway? The best results were obtained when letters were combined with phonemic awareness instruction. The NRP then, logically, considered that phonics.

I find it interesting that advanced phonemic awareness skills weren’t a focus of the phonemic awareness findings. In the years since, as phonemic awareness has had a greater focus, many of these advanced skills have been given a larger platform. It has also seemed that, in some cases, students have been receiving hours of additional intervention in the advanced areas of phonemic awareness. Most recently, questions have been raised about these practices. This leads me to believe the most worthy focuses of our instruction are as stated here: segmenting and blending. I will continue to use word ladders and word chaining in practice, with letters, but not so much as a phonemic awareness intervention, but as supported practice through our phonics studies. I also found it interesting that phonemic awareness instruction did not improve spelling for disabled readers and I wonder why that would be. I haven’t seen further information on this.

It’s also important to note- the increase in word recognition and reading comprehension is varied. The results identified above were for young students. After that, the results don’t lend themselves to phonemic awareness improving comprehension. With that said, improved comprehension would be a byproduct of improved decoding. The goal of phonemic awareness instruction isn’t comprehension improvement. Phonemic awareness is a small component of an overall reading program. The Panel was clear to identify phonemic awareness as a means to an end.

I have several posts where I go more into depth on phonological and phonemic awareness and give resources I’ve used. You may be interested in reading What is Phonological Awareness?, What is Phonemic Awareness?, 18 Non-Print Phonemic Awareness Activities for Early Readers, and Building Phonemic Awareness through Phonics

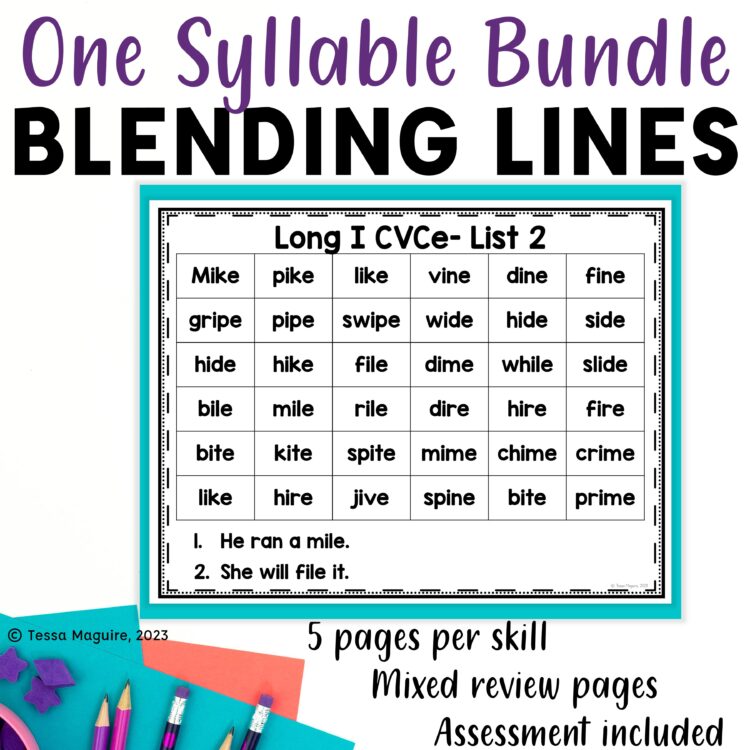

Phonics

Phonics uses the relationships between letters (graphemes) and sounds (phonemes) into text. It is used both for decoding (word reading) and encoding (spelling). The NRP examined 38 studies on phonics instruction and concluded that systematic phonics instruction gave children a faster start in learning to read compared to no instruction or instruction targeted to individual student needs. The panel also looked at synthetic (explicit) phonics and analytic (analogies) phonics. The panel found no strong difference between synthetic and analytic phonics results, but systematic approaches outperformed responsive approaches. Many different programs were used in these 38 studies, but the panel did not determine which programs were most effective> This is probably the most contested section of the NRP report and its findings are often misconstrued.

Phonics instruction improved kindergarten and first-grade children’s word recognition and spelling skills and had a positive impact on their reading comprehension. – Dr. Timothy Shanahan

This seems clear and expected evidence. I think this aligns with what every teacher ever would think. But let’s take a deeper look – especially since this quote only speaks to kinder and 1st grade.

The panel also identified that second graders, and older, at-risk readers also improved their word recognition, but did not demonstrate improvement in their overall reading comprehension. They concluded that phonics “failed to exert a significant impact on the reading performance of low-achieving readers in 2nd through 6th grades”. They also found a weak impact on reading and spelling for struggling readers in grades 2-6. These findings have been part of the pushback to the current focus on phonics with SoR.

As an educator, that has often worked with at-risk readers after 2nd grade, I think of many of my students when I read this. Is the phonics program being evaluated with older, at-risk students the same program that was used with them in the lower grades? If so, do the results suggest that program isn’t the right fit for that student, or that other deficiencies weren’t met? I have seen 5th graders soar when their phonemic awareness gaps were filled. Were those older students deficient in phonics and in need of that instruction? Or were these just below level readers and not necessarily in need of phonics instruction?

I also think it’s important to highlight this section from the Findings and Determinations by Topic Areas:

Systematic synthetic phonics instruction had a positive and significant effect on disabled readers’ reading skills. These children improved substantially in their ability to read words and showed significant, albeit small, gains in their ability to process text as a result of systematic synthetic phonics instruction. This type of phonics instruction benefits both students with learning disabilities and low-achieving students who are not disabled. Moreover, systematic synthetic phonics instruction was significantly more effective in improving low socioeconomic status (SES) children’s alphabetic knowledge and word reading skills than instructional approaches that were less focused on these initial reading skills.

In the recent renewed focus on the Five Pillars of Reading, I’ve read several things that suggest the focus on phonics doesn’t benefit many readers, citing the NRP findings given. I can see where they’re coming from. But, the above quote really negates that, for me. While all students don’t need the depth that systematic, synthetic phonics provides, it provides the instruction that all students benefit from. I think the recent push for systematic, sequential phonics has been with a focus on those students that did not learn to read through other methods to ensure we’re reaching ALL students.

I really appreciate Dr. Shanahan’s Practical Advice for Teachers in digesting what the NRP concluded in regards to phonics. Dr. Shanahan goes on to say three years of phonics is enough for most children, but that some struggling readers will need to continue longer. He also says that even proficient learners benefit from review, support with more complex words, and with spelling patterns in those complex words. He also likens successful decoding with learning a new language. I can successfully decode many words in Spanish, but that does not mean I understand what they mean. This could help explain the lack of comprehension improvement with older students in the provided studies. The words need to be part of the readers’ oral vocabulary to begin to impact reading comprehension.

When talking about phonics, it’s imperative that it’s applied to reading and writing. Phonics is a path to fluent reading and writing. It is a means to an end. Programs that focus too much on letters and sounds without enough application practice aren’t as effective. As well as, programs that focus strictly on phonics, and not enough on the other pillars of reading, aren’t going to build fluent readers.

The National Reading Panel goes on to say that it is “important that teachers be provided with evidence-based preservice training and ongoing inservice training to select and implement the most appropriate phonics instruction effectively”. Instruction must match students’ needs, and as the outcomes above suggest, we must be responsive in our instruction. Some students don’t need the same level and intensity of instruction as others. The effectiveness of phonics instruction, in large part, relies on the effectiveness of the teacher.

Fluency

Fluent readers are able to read orally with adequate speed, accuracy, and expression. Improper oral reading fluency is one of several factors that impact reading comprehension. As an instructional focus, fluency has often been a neglected area of reading.

Fluency instruction improved oral reading fluency itself, but it also had a positive impact on children’s decoding, word recognition, silent-reading comprehension, and overall reading achievement – Dr. Timothy Shanahan

In Dr. Shanahan’s Practice Advice for Teachers, he goes on to say that while fluency instruction does help low-achieving readers, it also has a positive influence on typically performing readers. The reviewed studies showed positive impacts with children from Grades 1-9.

Because the research methods varied so considerable from each other the fluency subgroup concluded that no conclusions could be drawn about the effectiveness of a specific method with a given age level. Instead, they did look at two instructional approaches: guided oral reading and independent silent reading.

Guided Oral Reading

The NRP looked at 16 studies of guided oral reading with contributions from 21 additional studies that didn’t meet the overall criteria for inclusion. They concluded that guided repeated oral reading routines that include guidance and feedback from teachers, peers, or parents had a significant and positive impact on word recognition, fluency, and comprehension across grade levels. The studies were conducted in both regular general education classrooms and special education settings and results were positive for all students- both those that were good readers and those experiencing reading difficulties. A variety of instructional materials were used. One caveat- there were no multi-year studies that gave information on the relationship between guided oral reading and fluency.

Many of the instructional practices included were ones you are probably familiar with: echo reading, paired reading, repeated reading, and more. No matter the specific instructional method, there are three essential components included:

- reading is oral, rather than silent

- includes repetition- students are asked to read and sometimes listen repeatedly

- students benefit from guidance or feedback

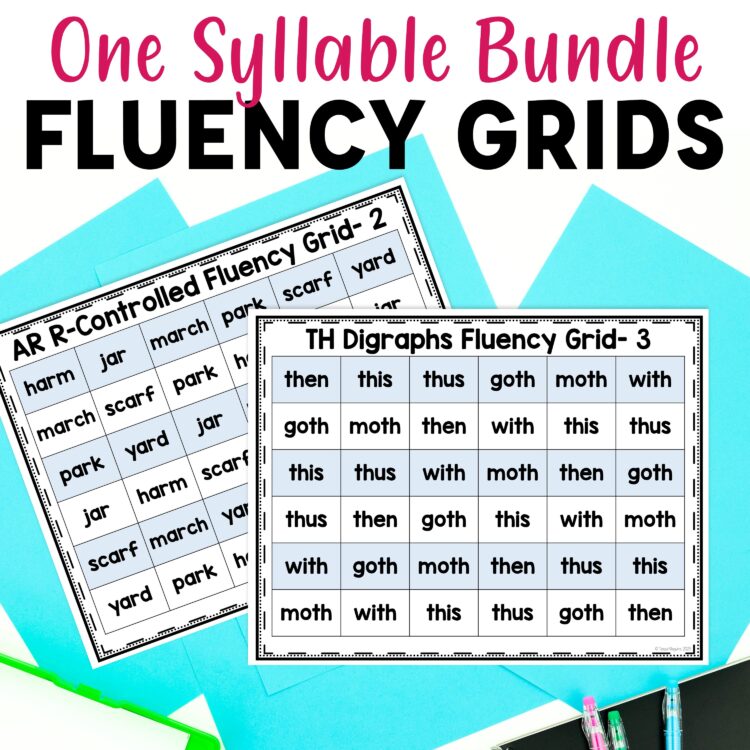

Looking for a program to support these fluency practices? I’ve found great results with HELPS Fluency. I used it one-on-one in an intervention setting, but it can be used (with training) by classroom assistants, paraprofessionals, or even parent volunteers!

Independent Silent Reading

There is a long held belief that students that engage in wide silent reading are stronger readers. However, much of the literature on the topic displays correlation between the two, rather than a deeper look into a causal relationship. The NRP wanted to address this issue. Unfortunately, there were no studies that met their criteria. However, 14 studies were examined to look for trends and outcomes from the data.

The NRP was unable to find a positive relationship between large amounts of independent reading and improvements in reading achievement, including oral reading fluency. The Panel urged researchers continue to explore this so that a definitive causal relationship could be explored.

The Fluent Reader by Dr. Tim Rasinski goes into depth with fluency practices. I did a blog series, several years back, into the book and its instructional implications. You can get follow along as you read at A Close Look at Fluency. I also created rubrics, used to give an overall grade on a students’ oral reading fluency in order to identify areas of needed instruction, and to be a more cohesive picture than just an automaticity score. You can read more about them and download them at Oral Reading Fluency Rubrics.

Comprehension

Comprehension is the end goal of reading. It’s also, arguably, the most complex aspect of reading. The NRP identified three themes in the research on reading comprehension: 1) that it is a complex, cognitive process that cannot be separated from vocabulary; 2) that it is an active process that requires an intentional and thoughtful interaction between both the text and the reader; and 3) that the preparation of teachers to better equip students to develop and apply comprehension strategies is linked to students’ achievement. These 3 subareas were evaluated.

Vocabulary Instruction

Much of our reading instruction focuses on words- namely decoding words. Vocabulary instruction, however, is focused on word meaning. Obviously, children learn many words without formal instruction. Incidental learning is obvious, and understandably impressive. While there is agreed upon number of words incidentally learned each year, it is known that more are learned incidentally than taught in school. With that said, we know that differences in environments during early formative years result in a large differences in vocabulary acquisition. The million word gap is well known, even outside of education communities.

There are two types of vocabulary- oral and print. A word can be correctly decoded, bit if it is not in the reader’s oral vocabulary, the reader will have to determine its meaning in an additional way. The larger the reader’s vocabulary, the easier it is to make sense of what’s being read. It is that understanding of the word that brings vocabulary under comprehension. The NRP looked at 50 studies that met their initial criteria, but there were many variables between them. The studies lead the Panel to give some suggestions but could not make the same clear results as some of other 5 pillars of reading. With that said, the NRP’s findings in regards to vocabulary are less contested than the other pillars, in my opinion.

The studies suggest that vocabulary instruction does lead to gains in comprehension, but the methods must be appropriate to the reader. They also found that computers were a more effective instructional tool than some traditional methods. The Panel also says that vocabulary can be learned incidentally through reading and listening to others read. Because vocabulary is learned incidentally, it’s also important to included opportunities for oral language within the school day.

The NRP gave several specific suggestions:

1) vocabulary should be taught directly and indirectly, through repetition and multiple exposures

2) learning through rich texts, and using computer technology to enhance vocabulary acquisition

3) direct instruction and

4) and dependence on a single instructional method is not effective.

Of course, it’s not possible for teachers to provide specific instruction for every word a student doesn’t know. Therefore, students need to be able to determine the meaning of unknown words. Students need to be proficient at using dictionaries and other tools, using knowledge of word parts, and how to use context clues. Of course, students need instruction on these word-learning strategies.

Text Comprehension Instruction

Finally, is the most complex area of reading: comprehension. Comprehension is the construction of meaning. It’s an interpretation of information through the filter of one’s own knowledge and beliefs. Comprehension is the end goal of reading instruction. It is reliant on each of the other 5 pillars of reading. Studies prove that each of these pillars influences how well students can construct meaning from the text.

The NRP looked to a whopping 205 studies on text comprehension instruction. In most of the studies, researchers ensured students could already decode the texts. Without successful decoding, we know comprehension will be impacted. From there, they were classified based on the kind of instruction. They identified 7 types of instruction that improve comprehension in “non-impaired readers”. An important distinction- many are more effective when used with other strategies. Good readers adjusts strategies as appropriate.

- Comprehension monitoring – also known as self-monitoring

- Cooperative learning

- Graphic and semantic organizers

- Question answering – plus, receiving immediate feedback on those answers

- Question generation

- Story structure

- Summarizing

The Panel was clear that more needed to be done with comprehension instruction. One area that they wanted a closer look was with comprehension within the content areas. Another is with the above strategies and specific age groups of students and specific text genres. Finally, and in my opinion the most importantly, the teacher’s role in comprehension instruction. Teachers have to be responsive to student needs and what the text requires. They need to be skilled at navigating their instruction in response to on the fly responses. Much as it’s discussed in the phonics pillar, the teacher is the critical component to effective instruction.

Why didn’t the NRP report end the reading wars?

The National Reading Panel report was the driver of many curricular changes and educational legislation. You can’t find a basal textbook that doesn’t claim to encompass the 5 pillars of reading. But the report also didn’t change all that much when you look at the large education landscape. In many cases, the report was ignored or made to fit in a specific “reading wars” narrative. It also didn’t get much public media attention. Outside of educators, most people don’t know about the report or its findings. For many reporters, it was too academic and complicated to be made clear to the public. Especially since most reporters didn’t have knowledge of reading instruction themselves.

For others, they viewed the NRP report as political. The report preceded the Bush administration’s education policy and NCLB and Reading First were implemented quickly after. “Scientifically-based reading research”, or SBRR, became a popular phrase – much like SoR has today. The NRP report helped justify those policies. But, most educators aren’t scientists and didn’t have access to the research nor time to understand it. States and local education agencies were slow to get on board with a seemingly politically-driven mandate. Reading First seemed to use the NRP report to identify specific phonics programs that should be used, which resulted in much controversy. A scandal ensued after RF members were found to be promoting curriculum that they had financial ties to. Reading First was not long lasting, and did not prove its effective. For the most part, neither was the attention to the NRP report.

Even within education, the NRP report was contested. There was disagreement with the “science” used. Joanne Yatvin, a member of the panel, issued a minority view. She states the panel review was “narrow” and disregarded language and literature. In the end, 432 studies on nine topics were reviewed and reported. She also stated the reviews were of limited usefulness to teachers and administrators (she was right). The findings were also not as clear cut as one would be lead to believe, especially today.

I especially appreciate the breakdown of The Federal Government Wants Me to Teach What? A Teacher’s Guide to the National Reading Panel Report. I find it to be a thorough evaluation of the NRP report, and breaks down why so much of it is contested. It even plainly states

“The NRP report, then, did not settle what is sometimes known as the ‘wars’. What the studies cited by yhe NRP show instead is that different approaches (phonics versus whole language) accomplish different goals.”

Want More on SoR?

At this point, the NRP report is now a twenty year old document. Newer understandings exist. With that said, the 5 pillars of reading are a solid place to begin your SoR journey and are truly essential components of effective reading instruction. Want to keep up as I explore key components of the Science of Reading? Get each post in the series your email by signing up below. First is my Introduction to the Science of Reading.

Send me the SOR series!

Signup for to receive each installment in my Introduction to the Science of Reading series.

Thank you!

You have successfully joined our subscriber list. Please check your email for the confirmation email. Check your spam folder for Tales from Outside the Classroom if you don’t see it.

You can read the report in its entirety here: Teaching Children to Read. The document is 449 pages long, but it’s detailed. The Findings and Determinations by Topic Areas is a much more digestible format from the NRP.

Further Reading on the National Reading Panel

National Reading Panel Report: Practical Advice for Teachers by Dr. Tim Shanahan

Why the National Reading Panel Report Didn’t Fix Reading Instruction by Will Callan

NRP Minority View by Joanne Yatvin

I Told You So: the Misinterpretation and Misuse of the National Reading Panel Report by Joanne Yatvin

The Federal Government Wants Me to Teach What? A Teacher’s Guide to the National Reading Panel Report by Diane Stevens

Put Reading First: The Rsearch Building Blocks for Teaching Children to Read

Newsletter Sign Up

Signup for my weekly-ish newsletter. I send out exclusive freebies, tips and strategies for your classroom, and more!

Please Read!

You have successfully joined our subscriber list. Please look in your e-mail and spam folder for Tales from Outside the Classroom. Often, the confirmation email gets overlooked and you're night signed up until you confirm!

Hi! I’m Tessa!

I’ve spent the last 15 years teaching in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd grades, and working beside elementary classrooms as an instructional coach and resource support. I’m passionate about math, literacy, and finding ways to make teachers’ days easier. I share from my experiences both in and out of the elementary classroom. Read more About Me.