© 2024 Tales from Outside the Classroom ● All Rights Reserved

The Need for Systematic, Sequential, and Explicit Phonics: Getting Started with the Science of Reading

It’s time we spend a little bit of time diving into phonics. Phonics is at the forefront of the Science of Reading conversations. In fact, when you hear someone talk about SOR, they may really only be talking about phonics. The science of reading instruction is about so much more than just phonics instruction. But, phonics hasn’t been enough of a focus in our classrooms over the last several decades, and our NAEP results show that our students are not proficient readers. This post aims to look at the research around phonics: what we learned from the NRP and what we’ve learned since.

English is an alphabetic writing system. Meaning, the sounds of the language are represented by letters (phonemes) or groups of letters (graphemes). When a child learns to decode that symbol-to-sound relationship, they have the ability to translate that written word into spoken language. Additionally, English is a deep orthography– there is a large amount of variation in phoneme-grapheme relationships.

With that said, almost 50% of English words have expected sound-symbol relationships. Another 36% percent have only 1 sound change that is unexpected. For one-syllable words, 80% are regular. Many variations can also become expected. For example, “bread” does not make the expected long vowel sound of the vowel team. However, knowing that many -ead words have the short e sound such as lead, read, head, and dead, makes the pronunciation more recognizable.

I don’t think there’s any pushback on teaching phonics. The question comes from how much, with whom, and for how long. In the post sharing the findings of the NRP, I talked about the surprising findings regarding phonics. Namely, its effectiveness beyond first grade. Since then, however, many additional meta-analyses have occurred evaluating various methodologies and the results of phonics instruction overall. Let’s review some of the findings:

- Systematic phonics yielded better gains than did nonsystematic or non-phonics instruction

- Systematic phonics was effective whether taught through one-on-one, small groups, or whole class settings

- Phonics instruction produced strong growth in kindergarten and 1st grade for students identified as at-risk for reading difficulties

- Positive effects were reported beyond first grade, though the magnitude of the gains were smaller

- Types of instruction did not result in significant performance differences

The types of instruction that were evaluated were:

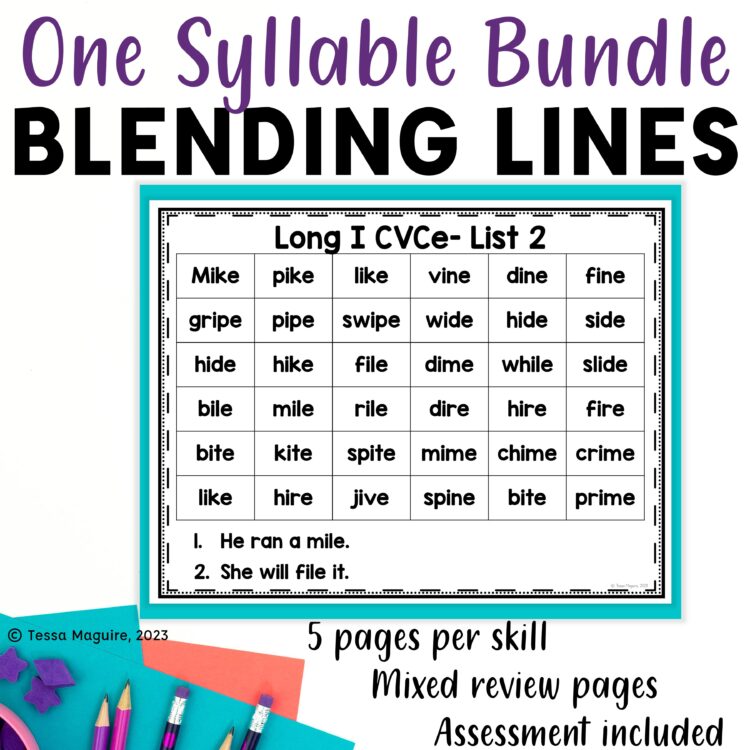

- Synthetic- connecting letters to sounds (graphemes to phonemes) and blending to form words

- Analytic- larger-unit phonics focusing on word families and onset-rime work.

- Embedded- supporting students with unknown words encountered in text

This quote stands out the most to me from the Findings and Determinations by Topic Areas:

Systematic synthetic phonics instruction had a positive and significant effect on disabled readers’ reading skills. These children improved substantially in their ability to read words and showed significant, albeit small, gains in their ability to process text as a result of systematic synthetic phonics instruction. This type of phonics instruction benefits both students with learning disabilities and low-achieving students who are not disabled. Moreover, systematic synthetic phonics instruction was significantly more effective in improving low socioeconomic status (SES) children’s alphabetic knowledge and word reading skills than instructional approaches that were less focused on these initial reading skills.

In that post, I talked about this quote being clear, for me, that synthetic phonics instruction was clearly what was needed for our students. While many students are able to learn to read without that level of explicit supports, others cannot. And we need to be sure we’re meeting the needs of all learners.

Research has continued to dive into phonics instruction, especially on the areas the NRP found to be lacking. Here’s a brief recap of some of the findings as presented in Dr. Susan Brady’s 2020 Perspective.

- Synthetic phonics instruction had significantly better reading, spelling, and phoneme awareness outcomes at the end of kindergarten intervention (and had positive long-term results) than analytic phonics. The children that received synthetic phonics instruction were the only ones that could read by analogy and did better reading irregular and nonsense words.

- Students receiving instruction on grapheme-phoneme correspondences had significantly better performance on advanced reading measures compared to students with orthographic rime programs and whole language programs. Despite the orthographic rime group receiving instruction focused on rimes, it was the students that received grapheme-phoneme instruction that were able to more fluently read transfer words with the same orthographic patterns. Finally, the students receiving grapheme-phoneme instruction performed significantly better on spelling and reading comprehension assessments.

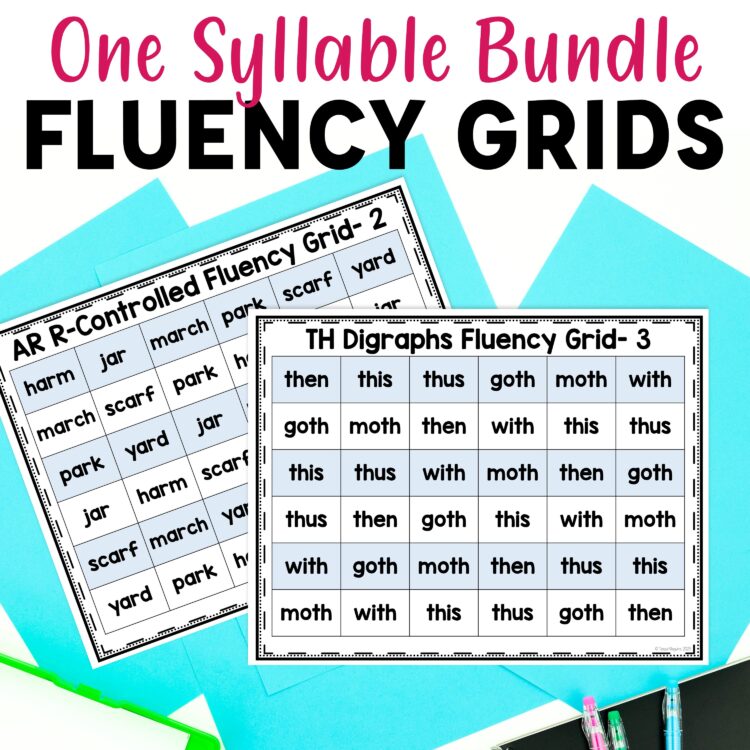

- Another study looked at students beyond 1st grade that had deficient decoding skills with one-syllable words. Researchers analyzed student errors by position within the word. After intervention targeting letter-sound concepts and phoneme awareness, students showed significant improvements with decoding, phoneme awareness, and comprehension in comparison to a control group.

- 1st grade students that were deficient in decoding would reach grade-level expectations at the end of second grade only if they received teacher-managed, code-based instruction in both 1st and 2nd grades.

- For students with weaknesses in phonics, explicit phonics intervention should be tailored to students’ needs. For older students, instruction should move beyond the grapheme-phoneme level into graphosyllabic patterns and morphological concepts.

- For students with significant reading difficulties, intensive intervention is necessary. Students in 2nd and 3rd grade that received intense intervention had long-term benefits demonstrated many years later.

What I appreciate about these findings is the evidence supporting phonics instruction beyond kindergarten and first grade, especially with students deficient with word recognition. These results are clear that a synthetic approach is more effective than analytic. That isn’t to say that an analytic program wouldn’t meet student needs. Rather, a synthetic approach is more effective for some students. Because of that, it’s what should guide our instruction to ensure we reach all learners. Additionally, analytic phonics plays a part in our instruction; it’s just not the instructional framework we should follow. We want students to notice patterns in words. It can be especially helpful with more advanced spelling patterns (e.g. eigh and should/would/could). But, our foundations needs to be on building the sound-spelling relationship and using analytic phonics to deepen that instruction.

How Much Phonics and For How Long?

Since the NRP report, we’ve also expanded our understanding of the progression of word reading development as demonstrated by Ehri’s Phases and her theory of orthographic mapping. We know that a students phase indicates the kind of instructional supports needed to help a student develop. Students in the prealphabetic and partial alphabetic need more phonics instruction than those at the consolidated phase. These students also need support with phonemic awareness. Whereas, students in the consolidated phase are ready to move towards instruction focused on morphology rather than phonics. It’s through this phase progression that our instruction shifts. A 4th grade student reading within the full alphabetic phase will need additional instruction than grade level peers, whereas a kindergarten student at the full alphabetic phase will not need much instruction.

We must assess our students to identify where they are in order to provide the kind of instruction needed to promote word reading development. Screening assessments help identify students in need of further instruction. Diagnostic assessments help us identify our specific students’ needs in order to differentiate our instruction and move beyond whole-class needs. I talk more about Diagnostic Phonics Assessments in their own post.

We know systematic, explicit instruction of grapheme-phoneme correspondences, following a developmental progression benefits decoding skills, phoneme awareness, and reading comprehension. We know it’s the instruction that benefits all learners. What’s still not clear is a specific scope and sequence. In the next post in the series, we’ll dive into how to structure our phonics lessons to benefit both reading and spelling.

Further Reading on Phonics Instruction

A 2020 Perspective on Research Findings on Alphabetics: Implications for Instruction Expanded Version by Dr. Susan Brady posted on The Reading League website

What Teachers Need to Know and Do to Teach Letter-Sounds, Phonemic Awareness, Word Reading, and Phonics by Dr. Linnea Ehri in The Reading Teacher Vol. 76 No. 1

The Alphabetic Principle: From Phonological Awareness to Reading Words on Improving Literacy

Speech to Print by Louisa Moats

Further Information on the Science of Reading

I am going to share helpful information on the Science of Reading throughout the next several months. Each post will have a different focus, and I will also share links to relevant posts of my own, from time to time. The topics have been carefully chosen to include the background information needed to understand the science and help you learn more about some of the large, underlying research in the field. The next three up in the series include The National Reading Panel’s 5 Pillars of Reading, the Simple View of Reading, and Scarborough’s Rope.

Want to get each post in your email so you don’t miss it? Sign up below. I will email you the posts and most relevant links each week after the post is live!

Send me the SOR series!

Signup for to receive each installment in my Introduction to the Science of Reading series.

Thank you!

You have successfully joined our subscriber list. Please check your email for the confirmation email. Check your spam folder for Tales from Outside the Classroom if you don’t see it.

‘

Newsletter Sign Up

Signup for my weekly-ish newsletter. I send out exclusive freebies, tips and strategies for your classroom, and more!

Please Read!

You have successfully joined our subscriber list. Please look in your e-mail and spam folder for Tales from Outside the Classroom. Often, the confirmation email gets overlooked and you're night signed up until you confirm!

Hi! I’m Tessa!

I’ve spent the last 15 years teaching in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd grades, and working beside elementary classrooms as an instructional coach and resource support. I’m passionate about math, literacy, and finding ways to make teachers’ days easier. I share from my experiences both in and out of the elementary classroom. Read more About Me.

One Comment