© 2024 Tales from Outside the Classroom ● All Rights Reserved

An Introduction: Getting Started with the Science of Reading (SOR)

The Science of Reading (SoR) is the new buzzword in education- especially at the elementary level. Most of what you likely see as the focus revolves around word recognition. Phonics & phonemic awareness are getting a lot of the attention, and for good reason. We have too many students that struggle to decode. But, there’s more to it. In this series of blog posts, I’m sharing some of the key ideas in the Science of Reading, where they have come from, and the science behind them.

An important disclaimer: I am not a reading researcher or cognitive scientist. The information I share here is not parsed from my own scientific studies. Rather, it’s my understanding of the information that it’s available, and I’ve done my best to ensure its accuracy. With each topic, I provide sources for additional reading and I encourage you to read them. As a teacher, our college instruction often didn’t include this information. Finding it out and putting all of the information together can be overwhelming & cumbersome. This series is designed to provide this information to teachers in an easy to digest and easily accessible way. With that said, I encourage you to spend time doing further reading by the researchers and scientists cited and exploring the links I provide.

What is the Science of Reading?

The Science of Reading is the (ever-growing) body of scientifically-based research into how we learn to read and why it works. It is both research and evidenced based instructional practices derived from thousands of studies from developmental psychology, educational psychology, linguistics, cognitive science, and cognitive neuroscience. It explains how proficient reading and writing develop, why some students struggle to learn to read and write, and how we can effectively improve student outcomes.

The Science of Reading is not new, though the buzzword is. It is based on decades of research. As our technology has grown, so has our ability to understand how the brain learns to read. We now better understand the areas of the brain involved in skilled reading and what happens with struggling readers.

The current focus of much on SOR is around phonics and/or phonemic awareness, largely due to the abundance of balanced literacy programs that did not provide systematic and sequential phonics instruction. We now know that 95% of all children can be taught to read by the end of first grade. We’re not meeting that mark and we should be. With that said, the Science of Reading is more than that. It encompasses all aspects of literacy- focusing on the five pillars of reading. It also frequently includes other aspects of E/LA or literacy, including spelling, grammar, and writing instruction.

There is a convergence of evidence of what works in teaching reading and it is:

phonological awareness: the ability to hear and manipulate the sounds in words

phonics: phoneme-grapheme correspondences

fluency: automatic and accurate word recognition with fluent expression

vocabulary and language comprehension

text comprehension

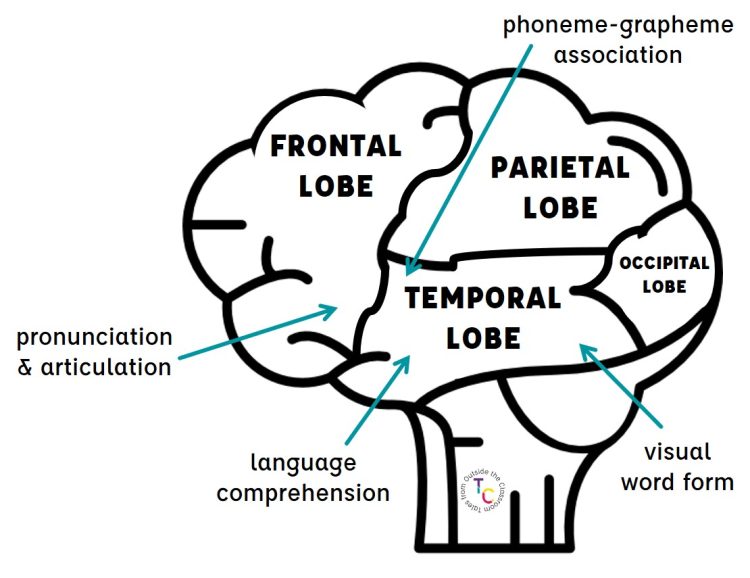

How the Brain Learns to Read

Over the last several years, our knowledge and understanding of how the brain acquires skills necessary for reading has grown. We now have a stronger understanding of the multiple areas of the brain that are involved in processing print, speech sounds, language, and meaning. We also know that learning to read is not a natural process. It must be taught. With explicit instruction and targeted practice neural pathways are built that allow for successful reading. By using evidence-based practices that are grounded in the science, we can help students develop strong reading skills and achieve better outcomes. The Science of Reading is based on this understanding of the brain.

Several major areas of the brain perform specific tasks together for reading to occur. The phonological processing system is two components: the area of the frontal lobe responsible for pronunciation and articulation, as well as the top-back part of the temporal lobe that is for phoneme-grapheme association. The visual word form area, or orthographic processing system, near the junction of the occipital and temporal lobes is responsible for recognizing letters and printed words. Finally, the planum temporale- at the junction of the parietal, occipital, and temporal lobes- is where the phonological and orthographic processing systems connect. This is critical for connecting phonemes to graphemes. We train these areas, through phonics instruction, to work together. When we try to have students do other things, such as using the picture to support their learning, we are activating other areas of the brain than needed for long-term retrieval.

The visual word form area of your brain connects what’s seen visually with the spoken language that’s already known. This area of our brains is surprisingly flexible, allowing us to recognize text at different sizes and orientations and even in different fonts. It also allows us to recognize words that are spelled incorrectly, or in atypical formats (such as all capital letters). But, we have to learn specific print variations explicitly. We have to learn that “ough” isn’t the same in “though”, “through”, “cough”, “rough”, etc. English is the most difficult alphabetic language in the world due to the variations between letter-sound correspondences.

This video by Professor Stanislas Dehaene gives a great introduction into how the brain learns to read. It gives great visuals of the brain and the areas activated while reading. Watch the first 15 minutes. It’s worth it!

The Science of Reading focuses on ensuring ALL students can read. Many practices miss the mark for many students. Guided reading works for some kids. If you were a balanced literacy educator, you’ve seen the proof in your classroom. But, while some practices work for some, they don’t work for all. We know that most reading difficulties can be prevented with explicit, targeted intervention work. Students of color, multi-language learners, and those from poverty fall behind and stay behind their white, middle class peers. According to the 2019 NAEP, only 35% of U.S. 4th graders scored “proficient”. This clearly demonstrates the need for a change in our habits. This is why this is such a focus in education.

What the Science of Reading is Not

The Science of Reading is not a specific philosophy or agenda. It’s not another “swing” in the pendulum or move in the “reading wars”. When we look to the science, those “wars” should end (they won’t). The Science of Reading is also not a specific program or curriculum. There are no “approved” reading curriculums that fit the science, nor is there some group that analyzes and evaluates curriculum. Every curriculum publisher is going to make the claim that their program is “research-based” or “evidence based” and many make the claim that they’re “aligned” with the Science of Reading. One must dig deeper to look into the embedded program and instructional practices before making decisions on programs. These statements are often based on causal relationships rather than true evidence.

As previously mentioned, there is more to reading instruction than phonics. A lack of adequate phonics instruction is clearly a social justice and equity issue that must be improved. But, I, personally, am worried about the growing focus on phonics instruction and hearing teachers identify foundational skills (or phonics and phonological awareness) programs as their new reading curriculum. Decoding and accurate word recognition is not the only component of word reading, and we cannot let an issue with effective practice for one area be the cause for ineffective practices in another. Our instruction must be cohesive and integrated.

Our instruction also must be responsive to our students’ needs. Students’ individual histories, cultural knowledge, interests, skills, and experience affect their responses to instruction and intervention. Teaching reading is not one size fits all. At the end of the day, highly successful teachers are our best tool against reading failure. Programs don’t teach; teachers do. Because of this, our instruction must follow the science.

My SOR Journey

I first started diving into this research when I was a young teacher interventionist. When I graduated college, I went through several days of DIBELS training as an instructional assistant, way back in 2005. The next year, as an interventionist, I was using that data to drive the reading interventions in my building. One of the areas I really focused on was phonemic awareness. It was all new to me, and I don’t think I learned much about phonics or phonemic awareness during my college years. Rather, I did a lot of reading myself, especially around the National Reading Panel (2000) report. At the time, the NRP report was fairly new. In the 20+ years since, not a lot has changed but we’ve continued to learn more and further refine our understanding of the NRP pillars. It’s been surprising, and disheartening, that so much of this has taken so long to be come widespread.

Over the years, I’ve continued to refine my learning. In the buildings I’ve worked in, I’ve continued to push for data focused interventions targeted to students true deficiencies. I have continued to advocate for true multi-tiered interventions. I’ve read a lot of things that I now know were not the best basis of my instruction. But I’ve also learned about a lot of strong, scientifically backed information. I have completed the Top Ten Tools for Teaching Reading program and am currently undergoing LETRS training. I also received my Masters degree in reading. I am by no means an expert and I still have a lot to learn. But, I’ve also learned a lot along the way!

Further Information on the Science of Reading

I am going to share helpful information on the Science of Reading throughout the next several months. Each post will have a different focus, and I will also share links to relevant posts of my own, from time to time. The topics have been carefully chosen to include the background information needed to understand the science and help you learn more about some of the large, underlying research in the field. The next three up in the series include The National Reading Panel’s 5 Pillars of Reading, the Simple View of Reading, and Scarborough’s Rope.

Want to get each post in your email so you don’t miss it? Sign up below. I will email you the posts and most relevant links each week after the post is live!

Send me the SOR series!

Signup for to receive each installment in my Introduction to the Science of Reading series.

Thank you!

You have successfully joined our subscriber list. Please check your email for the confirmation email. Check your spam folder for Tales from Outside the Classroom if you don’t see it.

Favorite Science of Reading books

Each of these books I’ve personally read and can attest to. Each Amazon link is an affiliate link, meaning I earn a small commission from your purchase at no additional cost to you.

Speech to Print by Louisa Moats

Uncovering the Logic of English by Denise Eide

The Knowledge Gap by Natalie Wexler

Phonics from A to Z: A Practical Guide by Wiley Blevins

On my To Be Read List

I wish I had enough time to finish all of the books I want to read. It’ll take me time, but I will get there. These books are on my list to read. Given how often I’ve seen them shared, I’m comfortable recommending them without having read them yet, myself.

Language at the Speed of Sight by Mark Seidenberg

The Writing Revolution by Judith Hockman & Natalie Wexler

The Reading Comprehension Blueprint by Nancy Hennessy

Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read by Stanislas Dehaene

Articles, Podcasts, Courses and More for Further Learning

Science of Reading: Defining Guide by The Reading League

Teaching Reading IS Rocket Science by Louisa Moats

Science of Reading: A Primer by Amplify – this contains fantastic brain representations of reading

Science of Reading by Amplify

Science of Reading the Podcast by Amplify

The Reading League YouTube Channel

Cox Campus: free virtual courses based on SOR

Science of Reading Virtual Workshops from Really Great Reading

Reading 101: self paced course by Reading Rockets

Reading Science and Educational Practice: Some Tenets for Teachers by Mark Seidenberg

Newsletter Sign Up

Signup for my weekly-ish newsletter. I send out exclusive freebies, tips and strategies for your classroom, and more!

Please Read!

You have successfully joined our subscriber list. Please look in your e-mail and spam folder for Tales from Outside the Classroom. Often, the confirmation email gets overlooked and you're night signed up until you confirm!

Hi! I’m Tessa!

I’ve spent the last 15 years teaching in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd grades, and working beside elementary classrooms as an instructional coach and resource support. I’m passionate about math, literacy, and finding ways to make teachers’ days easier. I share from my experiences both in and out of the elementary classroom. Read more About Me.

2 Comments

I am excited to see what your take is in everything you learned. I have read many of the books, and way back in ‘91 when I started teaching, I was trained in Whole Language, but the school I went to was teaching phonics . I taught basically SOR for the first 21 years of my career. Then I went to a large

district out of financial need with 4 kids going to college and was told I could not teach that way. (I snuck in what I could). I am excited that we are in the midst of a change.

I continue to find it so crazy that what I was learning and doing in 2005 and 2006 with DIBELS was so many of the right things and it’s now so many years later and there continues to not be an understanding of it. I hope you find some new-to-you information as I share! Thanks for joining in!