© 2024 Tales from Outside the Classroom ● All Rights Reserved

Ehri’s Phases of Word Reading Development: Getting Started with SoR

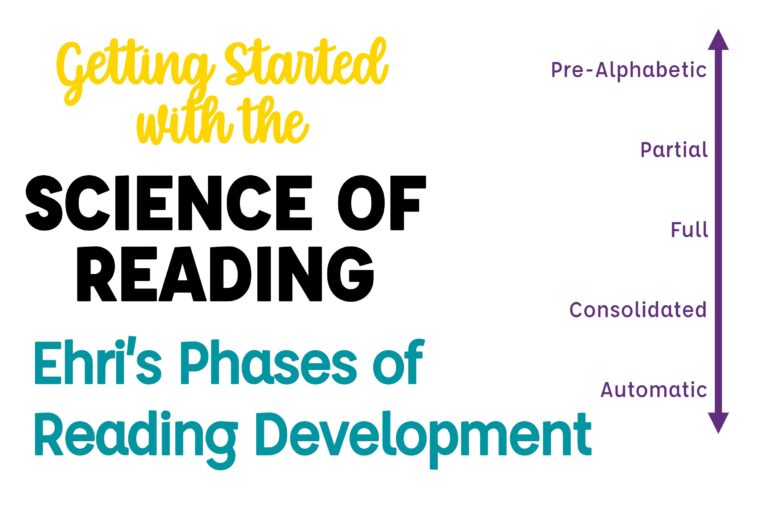

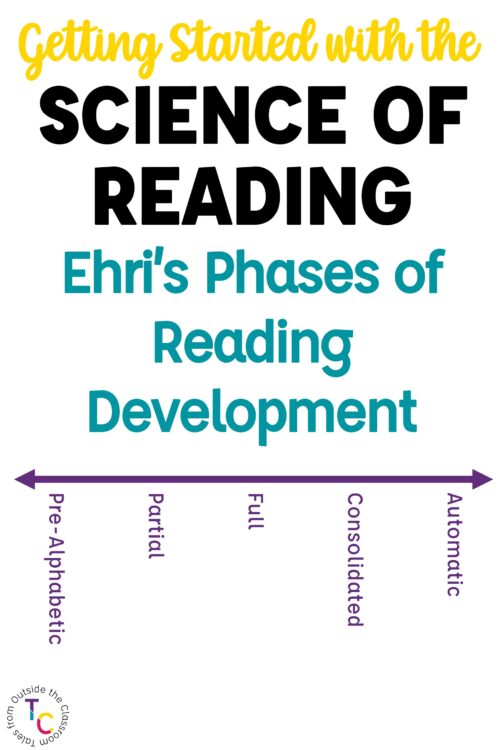

Last week we looked at Scarborough’s Rope. For the next several weeks, we’re going to focus on the word recognition strand. First up, is Ehri’s Phases for Reading Development. Dr. Linnea Ehri is a professor of psychology and has been studying the development of reading for over 4 decades. In her research, she identified 5 phases of reading skills development now commonly known as Ehri’s Phases or Ehri’s Phases of Reading Development. One note- this is sometimes referred to as 4 phases with the final phase being omitted.

The phases help us understand how children grow and develop on their path to proficient reading. Some children may move through the phases quickly, while others may need more time and additional, explicit instruction. Ehri’s phases identifies both phonemic awareness and phonics skills and reading behaviors at each level. Ehri’s phases help explain how words become “sight words” to beginning readers through orthographic mapping.

By understanding these reading phases we can become more proficient practitioners and help students in their progression. Ehri’s phases helps us understand the specific skills to target, scaffold, and support to guide students to the next phase. Understanding the phases of reading development also helps us understand a students’ errors. This is especially helpful with older, delayed readers, or those with a disability such as those with dyslexia. Rather than thinking of a “b/d reversal” as being a sign of dyslexia, one can understand that the student is still at the partial alphabetic or full alphabetic phase and that it’s a common mistake at that phase. Behaviors that might seem odd at that grade level are, in most cases, just behaviors indicative of a reader at an earlier phase of development.

The ways we learn to read words are developed together. If one way does not develop adequately, then others will not either. By understanding this, it helps us target our instruction at students’ deficiencies to help support their development.

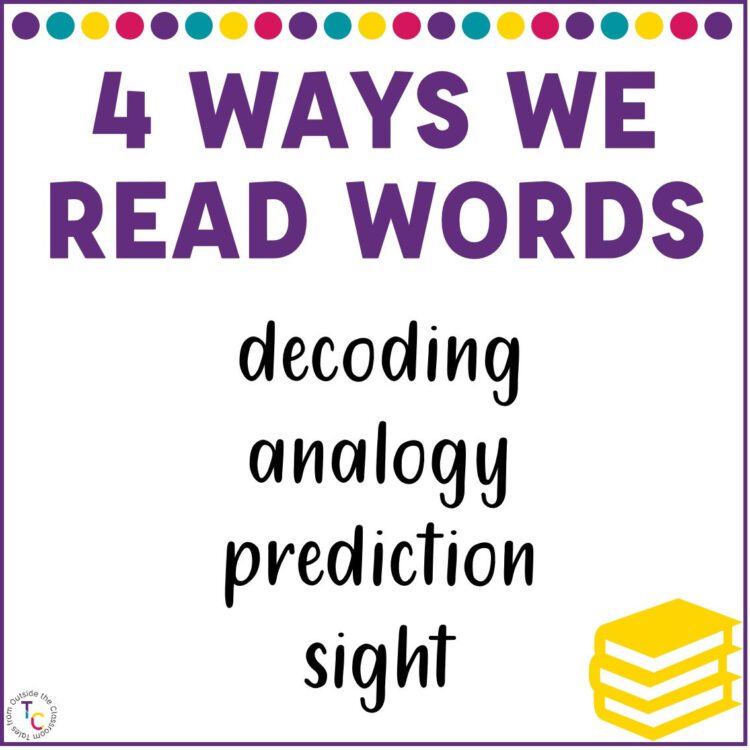

Ways we Read Words

Before understanding the phases of word reading development, it’s helpful to understand the ways we read words.

- Decoding: This is the strategy we think of most often when supporting readers in reading unknown words. It involves identifying the sounds of the presented graphemes and blending them into pronunciations of real words. In the earliest stages, these words are basic with letter-sound correspondences, but as readers grow the phonograms are more complex. Of course, decoding also including common affixes.

- Analogy: Another way of working with unfamiliar words is by analogy. This is especially helpful when a grapheme has more than one pronunciation. For example, to read “lead”, it may be connected with known word “read” to help with pronunciation. To make the analogy, readers access the known word from their memory and then adjust for the new word. Obviously, this means readers must have a bank of words with correct pronunciations already present in their memory.

- Prediction: A prediction is made by using some letters in the word, usually the initial ones, and context clues (both textual and pictorial) to predict. This is not particularly helpful as most words, especially those specific to content, cannot be guessed accurately. Just because this is a way we read, doesn’t mean it’s a way that should be explicitly taught to read.

- Sight: The final way to read words is by sight, which involves reading words that have been previously learned. For this to occur we must immediately connect its spelling, pronunciation, and meaning from our memory. Words read by sight don’t expend additional cognitive effort, which makes it especially valuable for making meaning. My next posts in this series cover orthographic mapping and common confusions regarding sight words which discuss this in more detail.

Ehri’s Phases of Reading Development

Pre-Alphabetic Phase

The first phase of Ehri’s phases, known as the pre-alphabetic phase, is characterized by a reader’s limited understanding of the alphabetic principle. Thus, its name is pretty clear: they are not yet knowledgeable about the alphabet. During this stage, young learners rely on visual cues, such as the appearance of a word or its unique features, rather than recognizing letters or understanding letter-sound relationships. They might recognize logos or signs and associate them with specific words or actions. For example, they can identify McDonald’s by the identifiable M logo or “read” Wendy’s on a sign or food bag. This phase has been referred to as logographic or reading at this phase as visual cue reading. Children at the pre-alphabetic phase see and read words as wholes, rather than as meaningful parts that come together. They lack the knowledge and ability to use letter names or sounds to form connections.

This phase is a typical part of early reading development. It is most commonly present in young children that have not yet started formalized instruction. Early in kindergarten most children move to the partial alphabetic phase, if not already there, based on explicit phonics and phonological awareness instruction.

Instructional Implications

- Provide instruction on the alphabetic principle explicitly teaching names and sounds of letters and connecting the two.

- Provide opportunities for writing, especially in conjunction with letters.

- Emphasize articulation of speech sounds using gestures and key words.

- Provide phonological awareness instruction using rhyming & alliteration. Games & nursery rhymes are helpful. For example, the Name Game song: “Sarah, Sarah, Bo Barah, Banana Fanna Fo Farah, Me mi mo Marah, Sarah”. Additional instruction should support onset-rimes and initial phoneme matching and isolation.

- Provide phonemic awareness instruction at the most basic levels- identifying initial and final sounds, counting sounds in short words, blending words with 2 or 3 sounds, deleting initial sounds, etc.

- Build vocabulary through rich read-alouds, theme units, and structured conversations.

Partial Alphabetic Phase

In the partial alphabetic phase, readers begin to connect letters with sounds, but only partially as the name suggests. Readers at this phase are weak at decoding and reading by analogy because both of these strategies rely stronger skills with the alphabetic principle than they possess. They recognize and use letter-sound relationships, but they are not yet proficient and make mistakes often. They likely have a strong grasp of “easy” consonants but struggle with commonly confused letters (i.e. b/d) and aren’t yet proficient with vowels. They may identify the initial letter in a word and then guess at the word using context- predictive reading as identified above.

Readers at this level begin to decode and encode simple VC and CVC words with known letters, though aren’t always accurate. Writing at this phase is not yet fully phonetic, but initial sounds and often final sounds are used. Letter names are often used to support spelling at this phase (i.e. TM as a spelling for “team”). “Caterpillar” may be spelled as “CRPR” because of the strong /er/ present in the sound in the word, though the child may be unable to read their writing back. Reading in this phase is referred to as phonetic cue reading because some letter-sound knowledge is used. This replaces the visual cue reading of the pre-alphabetic phase. Most typically progressing kindergarteners spend most of the year at the partial alphabetic phase, though some may move to the full level before the year is over.

Instructional Implications

- Ensure a robust exposure to print and texts through read alouds and shared reading experiences including retells and question-answer interactions after reading.

- Continue to provide instruction on the alphabetic principle explicitly teaching letter names and sounds.

- Provide instruction on phonemic awareness including phoneme segmentation and blending, as well as substitution, with words with 2 and 3 sounds.

- Provide opportunities for children to practice decoding and encoding words with corrective feedback. Encoding, in particular, should focus on connecting phonemes to graphemes. Words should be segmented, sounds counted, and then written. I have a post where I share some of my favorite ways to connect phonics and phonemic awareness at this phase: Building Phonemic Awareness through Phonics: Phoneme-Grapheme Activities

- Practice both regular and irregular high-frequency words to enable reading of connected text.

Full Alphabetic Phase

For typically developing readers, many enter the full alphabetic phase by late kindergarten or early first grade. They remain in this phase for much longer than in the previous phases. In the full alphabetic phase, readers have a good understanding of the alphabetic principle and attend to each letter in a given word. They can decode words by applying their knowledge of letter-sound relationships and blending those sounds together to form words.

However, reading at this stage can still be slow and laborious as children rely heavily on sounding out many words. Without a large bank of words in their “sight word vocabularies”, readers at this stage rely on their decoding skills. Through repeated exposures to words with taught phoneme-grapheme correspondences, “sight word vocabularies” are built once the words have been orthographically mapped. This is built, steadily and substantially, throughout this phase. As a reader’s skill grows, so does their ability to orthographically map words. When words are spelled as they are to be expected, the reader is able to map that word for memory much more quickly. Because of this, reading begins to become more fluent. Students also may still struggle with irregularly spelled words, or words with multiple pronunciations. To make this growth, students need practice with many phoneme-grapheme relationships. Students must read- a lot.

As mentioned, readers entering the full stage rely heavily on their decoding skills to read unknown words. But, during this phase, readers become able to read unfamiliar words by analogy. Words must be orthographically mapped as a sight word for students to make the analogy connection. Therefore, this is still not a strong decoding tool in the reader’s toolbox quite yet. However, it is being built throughout this stage for later use.

When you have an older, but poorly decoding student, this is often the phase where they remain. They have been able to add to their stored sight word vocabularies but struggle to learn and retain phoneme-grapheme correspondences. Delayed readers at this phase often rely on small visual cues and context to read text and aren’t attentive to the text at the level that’s needed. Because of this, they struggle to orthographically map the words for long term retrieval. For these students, it’s even more important to focus on phoneme-grapheme relationships and to map the sounds to spelling when both reading and building words. Explicit instruction mapping sounds to spelling helps support these delayed readers.

Instructional Implications

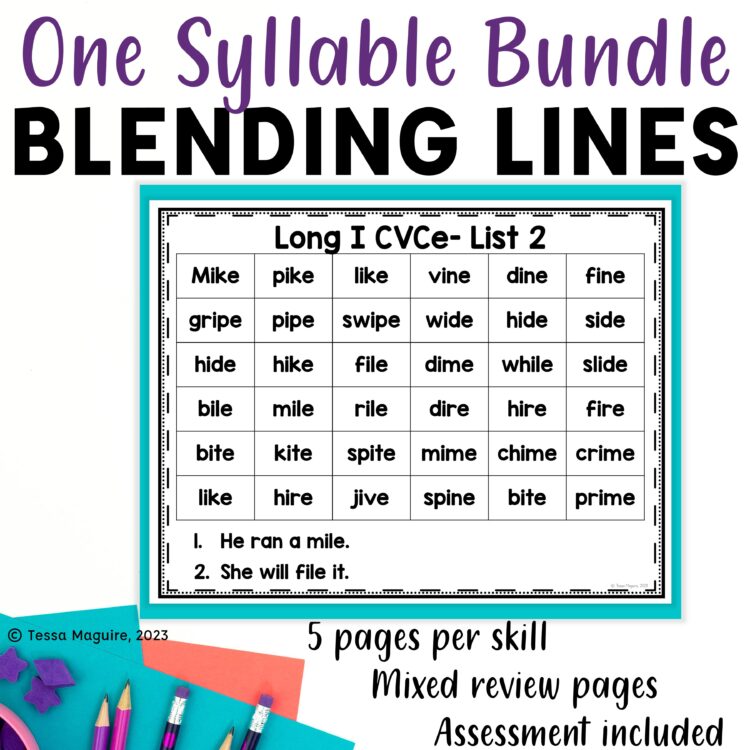

- Continue to provide instruction on the alphabetic principle explicitly teaching common graphemes and simple morphemes (such as “ed” and “ing”)

- Continue providing instruction on more advanced phonemic awareness tasks such as segmenting and blending words with blends and common difficult applications such as nasalized n. Advanced phonemic awareness skills such as manipulation need to be practiced and supported.

- Provide opportunities to practice decoding words in context and encoding words in isolation and in context. Continue to focus on connecting phonemes to graphemes to help map words. Words should be segmented, sounds counted, and then written, especially at the beginning work of this phase (word mapping). Find activities that connect sounds & spelling at this phase in my Building Phonemic Awareness through Phonics: Phoneme-Grapheme Activities post.

- Provide opportunities to decode and encode rimes (word families) to promote reading by analogy. This is one strategy and must not replace phoneme-grapheme based work.

- Provide explicit interactions with irregularly spelled words, forming connections between phonemes and graphemes that are known. Exceptional letters can then be identified and cued for future memory. I will detail more in a future post of its own.

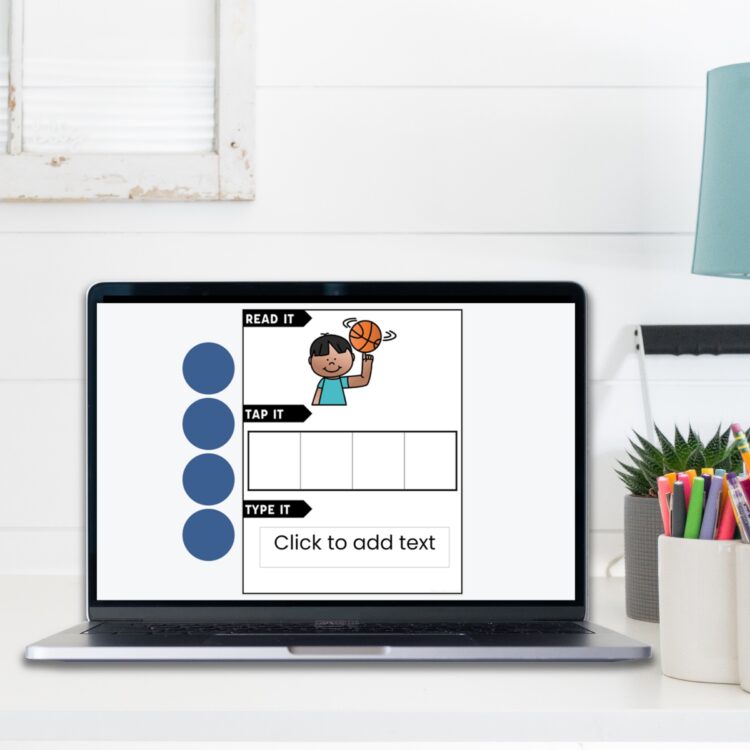

- Provide opportunities for students to read text with 95% accuracy- decodables are a must-have at this stage.

- Use a variety of literary texts including fiction, nonfiction, and poetry

Consolidated Alphabetic Phase

In the consolidated alphabetic phase, readers become more automatic and fluent in their word recognition skills and more efficient at decoding unknown words. They develop a large bank of sight vocabulary and no longer need to decode word by word while reading. They begin to recognize larger chunks of text, such as word families, syllables, and roots. These consolidated chunks are then used for more efficient decoding, rather than relying on individual phonemes. Another powerful component of this phase is the ability to make connections independent of instruction. Typically, this phase begins during second grade and continues to develop as readers become more automatic in their word reading skills.

Instructional Implications

- Help children learn to use their knowledge of word structure to decode and encode words of increasing complexity .

- Provide instruction on morphemic prefixes, suffixes, and roots. This helps students identify those phonograms when reading and spelling and identify the meaning of unknown words. This also helps build analogic reading in students as these become stored mentally for later retrieval.

- Provide opportunities to break apart multisyllable words by identifying the vowel and its adjacent consonants. As students practice, they build an awareness of morphemes and how syllables are frequently divided. Practice is more effective than memorizing syllabication rules.

- Advanced phonemic awareness skills such as deletion and manipulation are frequently

- Provide opportunities to practice reading words with fluency and automaticity

- Use materials that contain a variety of difficulty levels

For some readers, the consolidated alphabetic phase is where they encounter problems progressing. Typically, this is due to struggles with multi-syllable words – especially those with 4 and 5 syllables. These readers were able to rely on context and a large bank of words in their “sight word vocabularies” to progress to this phase. For these students, it’s even more important to focus on word-analysis. These students need explicit instruction and practice with prefixes and suffixes and identifying them in words. They need support in syllabication using those known affixes and practice using analogies to connect known words with unknown words.

Automatic Alphabetic Phase

The final phase in Ehri’s Phases is the automatic phase, which is characterized by proficient readers who can recognize and comprehend words quickly and effortlessly. At this stage, readers have developed a strong sight vocabulary, have a deep understanding of word structures, and can make connections between words with similar spellings and meanings. Unfamiliar words are decoded with automaticity. Academic or content-based words are decoded using a variety of effective strategies. At this phase, readers are able to focus entirely on meaning. Most proficient adolescent readers have reached the automatic phase.

It is important to note that these are general observed behaviors at each of Ehri’s Phases for Reading. Specific instructional strategies should be used based on student need and will vary from student to student, and as that student progresses. It’s also important to note the role of encoding. While often lagging behind decoding, learning phonics through word building and analogy helps students progress.

Want More on SoR?

Want to keep up as I explore key components of the Science of Reading? Get each post in the series your email by signing up below. First is my Introduction to the Science of Reading and then I dive into The 5 Pillars and the NRP, and the Simple View of Reading. My next posts in the series are going to continue take a deeper dive into the bottom strands of the reading rope- focusing on word recognition and decoding.

Send me the SOR series!

Signup for to receive each installment in my Introduction to the Science of Reading series.

Thank you!

You have successfully joined our subscriber list. Please check your email for the confirmation email. Check your spam folder for Tales from Outside the Classroom if you don’t see it.

Further Reading on Ehri’s Phases

Phases of Word Learning: Implications for Instruction with Delayed and Disabled Readers by Dr. Linnea Ehri & Dr. Sandra McCormick

What Teachers Need to Know and Do to Teach Letter-Sounds, Phonemic Awareness, Word Reading, and Phonics by Dr. Linnea Ehri in The Reading Teacher Vol. 76 No. 1

Development of Sight Word Reading: Phases and Findings by Dr. Linnea Ehri

How Children Learn to Read Words: Ehri’s Phases by Dr. Holly Lane

Ehri’s Phases of Word Development video by The Center for Literacy & Learning

Ehri’s Phases Lunch and Learn recording from The College of William & Mary

Ehri’s model of phases of learning to read: a brief critique by John R. Beech

Newsletter Sign Up

Signup for my weekly-ish newsletter. I send out exclusive freebies, tips and strategies for your classroom, and more!

Please Read!

You have successfully joined our subscriber list. Please look in your e-mail and spam folder for Tales from Outside the Classroom. Often, the confirmation email gets overlooked and you're night signed up until you confirm!

Hi! I’m Tessa!

I’ve spent the last 15 years teaching in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd grades, and working beside elementary classrooms as an instructional coach and resource support. I’m passionate about math, literacy, and finding ways to make teachers’ days easier. I share from my experiences both in and out of the elementary classroom. Read more About Me.